Brief history

On 28 September 1914 the German advance was halted by French troops at La Boisselle. There was bitter fighting for possession of the civilian cemetery, and for farm buildings on the south-western edge of the village known to the Germans as the Granathof or ŌĆśShell FarmŌĆÖ and to the French as the ŌĆśIl├┤tŌĆÖ.

A somewhat ghoulish German postcard depicting desperate fighting against French troops during the capture of La Boisselle by R.I.R.120 in September 1914. Image is copyright Jon Haslock and is reproduced with his permission.

In their efforts to retake the Il├┤t, in December 1914 French engineers began tunnelling beneath the ruins, beginning a prolonged struggle below ground that was to expand and deepen day by day until July 1916. With the war on the surface at stalemate, both sides continued to probe beneath the opponentŌĆÖs trenches and detonate ever-greater explosive charges, whilst at the same time protecting their own lines by underground warfare. When the British took over the Somme battlefront in August 1915, the French and Germans were working at a depth of 12m; the size of their charges had reached 3,000kg. No ManŌĆÖs Land was already an almost continuous line of mine craters for 375 metres.

Aerial photograph of the Glory Hole in August 1915. (Reproduced courtesy of Royal Engineers Museum & Library)

The British Tunnelling Companies deployed professional miners to extend and deepen the system, first to 24m and ultimately 30m.┬Ā Size of charges also increased – to over 6,000kg. Today, the bodies of many miners still lie deep beneath the crater fields.┬Ā Above ground the infantry occupied trenches just 45m apart, and lived in constant danger of snipers, mortar bombs and grenades above ground and enemy mines beneath. As a result of the incessant mutual hostility, maintenance of the advanced trenches on both sides of No ManŌĆÖs Land was difficult and perilous. For French, German, and British soldiers, La Boisselle was one of the most notorious sectors on the Western Front.

Tunnellers of 179 Tunnelling Company, Albert c.1916. (Image reproduced courtesy of Mrs G Hillman. Copyright Mrs G Hillman )

The Battle of the Somme

At the start of the Battle of the Somme La Boisselle stood on the main axis of British attack. The Germans had strongly fortified the cellars of the ruined houses, while the deeply-cratered ground of the Glory Hole made direct assault on the village impossible. To assist the attack the British therefore placed two massive mines, known as Y Sap and Lochnagar, on either flank. Despite their colossal size, the mines failed to help sufficiently neutralise the German defences in La Boisselle. When the 34thDivision attacked they suffered the worst losses of any unit on 1 July, itself the blackest day in British military history. After further costly assaults the ruins of La Boisselle were eventually captured on 4 July. Fighting returned to the Somme in March 1918 when the Germans retook the village, only to be forced back in August.

German soldiers of the 111th Reserve Infantry Regiment in the Granathof position. The lips thrown up by the mine craters can be seen behind them in no mans land, marked ŌĆśTrŌĆÖ. (Image reproduced courtesy Ralph J. Whitehead. Copyright Ralph J. Whitehead).

Post-war

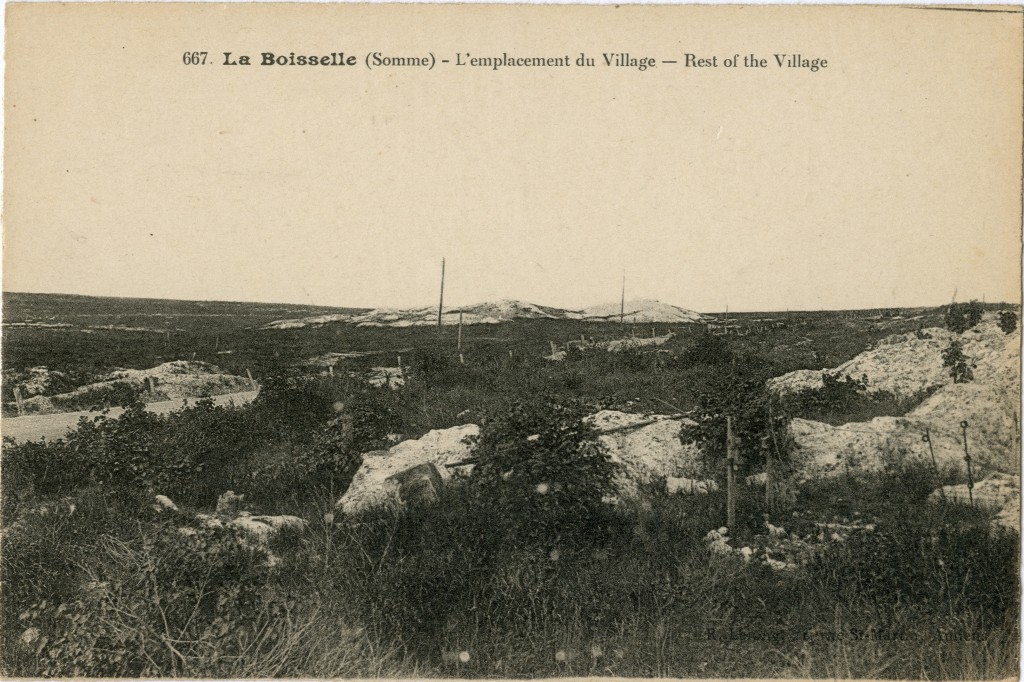

Unsuitable for cultivation, after the war the area of the Glory Hole was gradually bought by the Lejeune family. In the 1920s they backfilled the trenches but left the crater field untouched. Since that time the ground has only ever been employed for orchards or grazing.┬Ā In the 1930s there was a proposal to acquire part of the site for a memorial to the 34th Division.┬Ā In 1936 at a special ceremony to commemorate transfer of the sector from French to Scottish troops in July and August 1915, soil from the Glory Hole was mixed with earth from the recruiting areas of the Breton 19th Infantry Regiment (Brest in Brittany) and the Black Watch (Aberfeldy in Perthshire): the deep Celtic bond forged 20 years before was still strong. Two urns were specially made for the symbolic exchange. The logo of the La Boisselle Study Group is based upon the urn which still survives in the Black Watch Museum in Perth.

As more land has been reclaimed by the plough or developed for housing, areas of virgin battlefield containing both opposing trenches and the dramatic evidence of mine fighting have become extremely rare on the Western Front. It was this situation, combined with a profound affinity with the Glory Hole developed over many decades through the annual visits of veterans, that prompted the proprietors to request the La Boisselle Study Group to help research and preserve the land.

The Glory Hole in March 1916

An officer of the 1st Dorsets describes the Glory Hole in March 1916:

At Millencourt I learned something of the reputation of the La Boisselle trenches. They were among the most notorious in the British lines. For a considerable distance the opposing lines were divided only by the breadth of the mine craters: the British posts lay in the lips of the craters protected by thin layers of sandbags and within bombing distance of the German posts; the approaches to the posts were shallow and waterlogged trenches far below the level of the German lines, and therefore under continuous observation and accurate fire by snipers. Minenwerfer bombs of the heaviest type exploded day and night on these approaches with an all-shattering roar. The communication trenches were in fact worse than the posts in the mine craters to most people; there were, however, some who always felt a certain dislike of sitting for long hours of idleness on top of mines which might at any moment explode. In the craters movement of any kind in the daytime was not encouraged. The four company commanders and the colonel went up to examine the trenches and reported on them unfavourably. The colonel stated that in his long experience they were the worst trenches which he had ever seen.

In the afternoon I and a companion went forward to inspect the mine craters, which my company was to take over in the course of the night. We passed down our front-line trench towards the ruins of the cemetery through which our line ran. East of the cemetery was the heaped white chalk of several mine craters. Above them lay the shattered tree stumps and litter of brick which had once been the village of La Boisselle. We progressed slowly down the remains of a trench and came to the craters, and the saps which ran between them. Here there was no trench, only sand-bags, one layer thick, and about two feet above the top of the all-prevailing mud. The correct posture to adopt in such circumstances is difficult to determine; we at any rate were not correct in our judgement, as we attracted the unwelcome attentions of a sniper, whose well-aimed shots experienced no difficulty in passing through the sand-bags. We crawled away and came in time to a trench behind the cemetery, known as Gowrie Street. Liquid slime washed over and above our knees; tree trunks riven into strange shapes lay over and alongside the trench. The wintry day threw greyness over all. The shattered crosses of the cemetery lay at every angle about the torn graves, while one cross, still erect by some miracle, overlooked the craters and the ruins of La Boisselle. The trenches were alive with men, but no sign of life appeared over the surface of the ground. Even the grass was withered by the fumes of high explosive. Death indeed, was emperor here.

Charles Douie, The Weary Road, John Murray, London,1929

Tunnelling ŌĆō the subterranean world

Captain Stanley Bullock, 179 Tunnelling Company describes the conditions underground:

At one place in particular our men swore they thought he was coming through, so we stopped driving forward and commenced to chamber in double shifts.┬Ā We did not expect to complete it before he blew, but we did.┬Ā A chamber 12′ x 6′ x 6′ in 24 hours.┬Ā The Germans worked for a shift more than we did and then stopped. They knew we had chambered and were afraid we should blow and no more work was done there. I used to hate going to listen in that chamber more than any other place in the mine. Half an hour, sometimes once sometimes three times a day, in deadly silence with the geophone to your ears, wondering whether the sound you heard was the Boche working silently or your own heart beating.┬Ā God knows how we kept our nerves and judgment.┬Ā After the Somme attack when we surveyed the German mines and connected up to our own system, with the theodolite we found that we were 5 feet apart, and that he had only started his chamber and then stopped.